Aldo Moro

| Aldo Moro | |

|

|

|

61st and 55th

Prime Minister of Italy |

|

|---|---|

| In office 4 December 1963 – 24 June 1968 |

|

| President | Antonio Segni Giuseppe Saragat |

| Deputy | Pietro Nenni |

| Preceded by | Giovanni Leone |

| Succeeded by | Giovanni Leone |

| In office 23 November 1974 – 29 July 1976 |

|

| President | Giovanni Leone |

| Deputy | Ugo La Malfa |

| Preceded by | Mariano Rumor |

| Succeeded by | Giulio Andreotti |

|

Minister of Justice

|

|

| In office July 6, 1955 – May 15, 1957 |

|

| Prime Minister | Antonio Segni |

| Preceded by | Michele De Pietro |

| Succeeded by | Guido Gonella |

|

Minister of Education

|

|

| In office May 19, 1957 – February 15, 1959 |

|

| Prime Minister | Adone Zoli Amintore Fanfani |

| Preceded by | Paolo Rossi |

| Succeeded by | Giuseppe Medici |

|

Minister of Foreign Affairs

|

|

| In office December 28, 1964 – March 5, 1965 |

|

| Prime Minister | Himself |

| Preceded by | Giuseppe Saragat |

| Succeeded by | Amintore Fanfani |

| In office December 30, 1965 – February 23, 1966 |

|

| Prime Minister | Himself |

| Preceded by | Amintore Fanfani |

| Succeeded by | Amintore Fanfani |

| In office July 7, 1973 – November 23, 1974 |

|

| Prime Minister | Mariano Rumor |

| Preceded by | Giuseppe Medici |

| Succeeded by | Mariano Rumor |

|

Minister of the Interior

|

|

| In office February 12, 1976 – July 29, 1976 |

|

| Prime Minister | Himself |

| Preceded by | Luigi Gui |

| Succeeded by | Francesco Cossiga |

|

|

|

| Born | September 23, 1916 Maglie, Kingdom of Italy |

| Died | May 9, 1978 (aged 61) Rome, Italy |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Political party | Christian Democracy |

| Religion | Roman Catholic |

Aldo Moro (September 23, 1916 – May 9, 1978) was an Italian politician and the 55th and 61st Prime Minister of Italy, from 1963 to 1968, and then from 1974 to 1976. He was one of Italy's longest-serving post-war Prime Ministers, holding power for a combined total of more than six years.

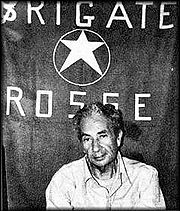

One of the most important leaders of Democrazia Cristiana (Christian Democracy, DC), Moro was considered an intellectual and a patient mediator, especially in the internal life of his party. He was kidnapped on March 16, 1978, by the Red Brigades (BR), and killed by them after 54 days of captivity.

Contents

|

Early career

Moro was born in Maglie, in the province of Lecce (Puglia). During the later period of fascism, he was member of the Gioventù Universitaria Fascista (GUF) university groups. He studied Law at the University of Bari, an institution where he was later to hold the post of ordinary professor. His political career started in 1941 when he became president of the FUCI (Federation of Catholic University Students). After several years forging an academic career in Bari he, together with friends, established the periodical La Rassegna which was to be published until 1945. After World War II, Moro was elected to the Constituent Assembly in 1946, and helped to draft the Italian constitution. He was then re-elected as a member of the House of Representatives in 1948, where he served as a member until his violent death.

Historic compromise

During the 1970s, he was one of the political leaders who gave the deepest attention to Enrico Berlinguer's project of a so-called Compromesso Storico (historic compromise). The leader of the Partito Comunista Italiano (PCI, Italian Communist Party), which had obtained 34.4% of the vote in the June 1976 general election, had proposed solidarity between Communists and Christian Democrats during a period of serious economic, social and political crisis in Italy. Moro, then the president of DC, was one of those who had helped to find a way to finally form a government of "national solidarity".

As leader of the parliamentary coalition he served as Prime Minister from 1963 to 1968, and again from 1974 to 1976.

Kidnapping and death

Kidnapped, March 16, 1978

On March 16, 1978, Moro was kidnapped, after the murder of his five bodyguards, on Via Fani, a street in Rome, by a militant communist group known as the Red Brigades led by Mario Moretti. At the time, all of the founding members of the Red Brigades were in jail, and the group that kidnapped Moro is therefore known as the "Second Red Brigades." Moro was kidnapped on his way to a session of the House of Representatives, where a discussion was supposed to take place regarding a vote of confidence in a new government led by Giulio Andreotti (DC) and with, for the first time, the support of the Communist Party. It was the first implementation of Moro's strategic vision as defined by the Compromesso storico (historic compromise).

In the following days, trade unions called for a general strike, while security forces made hundreds of raids in Rome, Milan, Turin and other cities searching for Moro's location. Held for two months, he was allowed to send letters to his family and politicians. The government refused to negotiate, despite demands by family, friends and Pope Paul VI.[1] In fact, Paul VI "offered himself in exchange … for Aldo Moro …"[2] During the investigation of Moro's kidnapping, General Carlo Alberto Dalla Chiesa reportedly responded to a member of the security services who suggested torture against a suspect, "Italy can survive the loss of Aldo Moro. It would not survive the introduction of torture."[3][4] The Red Brigades initiated a secret trial. Moro was found guilty and sentenced to death. They then sent demands to the Italian authorities, which stated that unless 16 Red Guard prisoners were released, Moro would be executed. The Italian authorities responded with a manhunt.[5]

After 54 days of detention, Moro was murdered in or near Rome on May 9. His body was found later that day in a parked car, left with apparent symbolism, between the headquarters of the DC and the PCI on Rome's Via Caetani. He had been shot in the chest 11 times.

Negotiations

The Red Brigades (BR) proposed to exchange Moro's life for the freedom of several imprisoned terrorists. During his detention, there has been speculation that many knew where he was (an apartment in Rome). When Moro was abducted, the government immediately took a hard line position: the "State must not bend" on terrorist demands. Some contrasted this with the kidnapping of Ciro Cirillo in 1981, a minor political figure for whom the government negotiated. However, Cirillo was released for a monetary ransom, rather than the release of imprisoned terrorists.

Romano Prodi, Mario Baldassarri,[6] and Alberto Clò, of the faculty of the University of Bologna passed on a tip about a safe-house where the BR might have been holding Moro on April 2. Bizarrely, Prodi claimed he had been given the tip by the founders of the Christian Democrats, from beyond the grave in a seance and a Ouija board, which gave the names of Viterbo, Bolsena and Gradoli.[7] This is widely viewed as being an attempt to hide Romano Prodi's contacts amongst the far-left.[7]

Aldo Moro's captivity letters

During this period, Moro wrote several letters to the leaders of the Christian Democrats and to Pope Paul VI (who later personally officiated in Moro's Funeral Mass). Those letters, at times very critical of Andreotti, were kept secret for more than a decade, and published only in the early 1990s. In his letters, Moro said that the state's primary objective should be saving lives, and that the government should comply with his kidnappers' demands. Most of the Christian Democrat leaders argued that the letters did not express Moro's genuine wishes, claiming they were written under duress, and thus refused all negotiation. This was in stark contrast to the requests of Moro's family. In his appeal to the terrorists, Pope Paul asked them to release Moro "without conditions".

It has been conjectured that Moro used these letters to send cryptic messages to his family and colleagues. Doubts have been advanced about the completeness of these letters; Carabinieri General Carlo Alberto Dalla Chiesa (later killed by the Mafia) found copies of the letters in a house that terrorists used in Milan, and for some reason this was not publicly known until many years later.

Via Caetani, equidistant between DC and PCI

When the Red Brigades decided to execute Moro, they placed him in a car and told him to cover himself with a blanket, that they were going to transport him to another location. After Moro was covered, they emptied ten rounds into him, killing him: the killer was Mario Moretti. Moro's body was left in the trunk of a car in Via Caetani, a site equidistant between the Christian Democratic Party and the Communist Party headquarters (), as a last symbolic challenge to all those who, like Moro, had an inclination to include the Communist party in the government of Italy jointly with the Christian Democratic party, that had been the main political party in government since World War II. After the recovery of Moro's body, the Minister of the Interior Francesco Cossiga resigned, gaining trust from the Communist party, which would later make him the first President of the Republic to be elected at the first ballot.

Antonio Negri's 1979 arrest and release

On April 7, 1979, Marxist philosopher Antonio Negri was arrested along with other leaders of Autonomia Operaia, (Oreste Scalzone, E. Vesce, A. Del Re, L. Ferrari Bravo, Franco Piperno and others). Pietro Calogero, an attorney close to the PCI, accused the Autonomia group of masterminding left-wing "terrorism" in Italy. Negri was charged with a number of offences including leadership of the Red Brigades, being behind Moro's kidnapping and murder and plotting to overthrow the government. A year later, he was found innocent of Moro's assassination.

In the New York Review of Books, Thomas Sheehan wrote at the time in Negri's defense, "Negri is a figure of some stature in Italy, and his arrest might be compared, imperfectly, to jailing Herbert Marcuse a decade ago on suspicion of being the brains behind the Weathermen."

In the same journal in 2003, Alexander Stille accused Negri of bearing moral but not legal responsibility for the crimes, citing Negri's words from one year later:

Every action of destruction and sabotage seems to me a manifestation of class solidarity.... Nor does the pain of my adversary affect me: proletarian justice has the productive force of self-affirmation and the faculty of logical conviction.

and

The antagonistic process tends toward hegemony, toward the destruction and the annihilation of the adversary.... The adversary must be destroyed.[8]

Alternative points of view about Moro's death

Many other theories have been advanced about Moro's death.

The "Gladio network", directed by NATO, has also been accused. Historian Sergio Flamigni, an erstwhile communist party member, believes Moretti was used by Gladio in Italy to take over the Red Brigades and pursue a strategy of tension. In BR member Alberto Franceschini's book,[9] Aldo Moro is described as one of Gladio's founders. Evidence has emerged to support this view of American involvement in the overarching the strategy of tension, and of known strong American foreign policies against the then looming historic (unprecedented in post war times) coalition that would have admitted the eurocommunist PCI into a government of national unity, the fear on the U.S. side being that Italy thereafter might withdraw from NATO and that the U.S. would have then lost access to vital Mediterranean ports.[10] Moro's widow later recounted Moro's meeting with U.S. President Nixon's advisor, Henry Kissinger, and an unidentified American intelligence official, who warned him not to pursue the strategy of bringing the Communist Party into his cabinet,[11] telling him "You must abandon your policy of bringing all the political forces in your country into direct collaboration...or you will pay dearly for it." Moro was allegedly so shaken by the comment that he became ill and threatened to quit politics.[12]

Mino Pecorelli's May 1978 article

Investigative journalist Mino Pecorelli thought that Aldo Moro's kidnapping had been organised by a "lucid superpower" and was inspired by the "logic of Yalta". He painted the figure of General Carlo Alberto Dalla Chiesa as "general Amen", explaining in his review, the Osservatorio politico, in an article titled "Vergogna, buffoni!" (Shame on you, buffoons!), that it was Dalla Chiesa that, during Aldo Moro's kidnapping, had informed the then Interior Minister Francesco Cossiga of the location of the cave where Moro was detained. But he would have been ordered not to act on his information because of the opposition of a "lodge of the Christ in Paradise." The allusion to Propaganda Due masonic lodge was clear. Pecorelli then wrote that Dalla Chiesa was also in danger and would be assassinated (Dalla Chiesa was murdered four years later). After Aldo Moro's assassination, Mino Pecorelli published some confidential documents, mainly Moro's letters to his family. In a cryptic article published in May 1978, wrote The Guardian in May 2003, Pecorelli drew a connection between Gladio, NATO's stay-behind anti-communist organisation (whose existence was publicly acknowledged by Prime Minister Giulio Andreotti in October 1990) and Moro's death.[13] During his interrogation, Aldo Moro had referred to "NATO's anti-guerrilla activities." Mino Pecorelli, who was on Licio Gelli's list of P2 members discovered in 1980, was assassinated on March 20, 1979. The ammunitions used for Pecorelli's assassination, a very rare type, were the same as those discovered in the Banda della Magliana 's weapons stock hidden in the Health Minister's basement. Pecorelli's assassination has been thought to be directly related to Giulio Andreotti, who was condemned to 24 years of prison for homicide in 2002 [14] before having the sentence cancelled by the Supreme Court of Cassation in 2003.

Carlos "the Jackal" speaks to ANSA

In a 2008 interview with the Italian news network ANSA (news agency), Venezuelan terrorist Carlos the Jackal stated from his cell in the prison at Poissy[15][16] that there had been a deal to exchange Aldo Moro for several imprisoned members of the Red Brigades. Under the terms of the deal struck with "patriotic" members of the Italian military intelligence agency SISMI (Carlos' words), several Italian servicemen and members of a Palestinian resistance group would escort the prisoners to an Arab country. The deal fell through while the plane sat on a runway in Beirut, perhaps because a PLO official's loose tongue alarmed a "pro-NATO" faction within SISMI. (Carlos maintains that NATO wanted Moro dead, while the Soviets wanted him alive.) The officials in charge of the operation were subsequently purged or forced to resign.

Carlos also claimed that the plotters originally planned to kidnap, along with Moro, the industrialist Gianni Agnelli and a judge of the Italian Supreme Court. He expressed surprise to learn that the Catholic Church was ready to pay a "huge" (ingente) ransom for Moro's release.

"Sacrifice Aldo Moro to maintain the stability of Italy"

Steve Pieczenik, a former member of the U.S. State Department sent by President Jimmy Carter as a "psychological expert" to integrate the Interior Minister Francesco Cossiga's "crisis committee", was interviewed by Emmanuel Amara in his 2006 documentary Les derniers jours d'Aldo Moro ("The Last Days of Aldo Moro"), in which he stated that:

We had to sacrifice Aldo Moro to maintain the stability of Italy.[17][18]

He added that the U.S. had to "instrumentalize the Red Brigades," and that the decision to have him killed was taken during the fourth week of Moro's detention, when he started revealing state secrets through his letters [19] (allegedly the existence of Gladio).[18] Francesco Cossiga also admitted the "crisis committee" also leaked a false statement, attributed to the Red Brigades, saying that Moro was dead.[11] [20]

Cinematic adaptations

A number of films have portrayed the events of Moro's kidnapping and murder, with varying degrees of fictionalization:

- Todo modo (1975), directed by Elio Petri, in which the character of the president is evidently inspired by Aldo Moro. The film is based on a novel by Leonardo Sciascia.

- Il caso Moro (1986), directed by Giuseppe Ferrara and starring Gian Maria Volonté as Moro.

- Year of the Gun (1991), directed by John Frankenheimer.

- Broken Dreams (Sogni infranti, 1995), a documentary directed by Marco Bellocchio.

- Five Moons Plaza (Piazza Delle Cinque Lune, 2003), directed by Renzo Martinelli and starring Donald Sutherland.

- Good Morning, Night (Buongiorno, notte, 2003), directed by Marco Bellocchio, portrays the kidnapping largely from the perspective of one of the kidnappers.

- Romanzo Criminale (2005), directed by Michele Placido, portrays the authorities finding Moro's body.

- Emmanuel Amara, Les derniers jours d'Aldo Moro (The Last Days of Aldo Moro), 2006

- Il Divo : La Straordinaria vita di Giulio Andreotti, directed by Paolo Sorrentino, 2008

Streets named for Aldo Moro

Malta: an eight-lane road in the South of Malta. Vicenza: a four-lane road in eastern Vicenza. Bari: Piazza Aldo Moro Rome: Piazzale Aldo Moro (site of La Sapienza University)

References

- ↑ 1978: Aldo Moro snatched at gunpoint, "On This Day", BBC (English)

- ↑ Holmes, J. Derek, and Bernard W. Bickers. A Short History of the Catholic Church. London: Burns and Oates, 1983. 291.

- ↑ Report of Conadep (National Commission on the Disappearance of Persons): Prologue - 1984

- ↑ Quoted in Dershowitz, AM Why Terrorism Works, p134 ISBN 9780300101539

- ↑ 100 Years of Terror - A documentary by History Channel

- ↑ June 17, 1998 hearing of the Commissione parlamentare d'inchiesta sul terrorismo in Italia e sulle cause della mancata individuazione dei responsabili delle stragi directed by senator Giovanni Pellegrino (Italian)

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Popham, Peter (2 December 2005). "The seance that came back to haunt Romano Prodi". London: The Independent. http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/the-seance-that-came-back-to-haunt-romano-prodi-517786.html. Retrieved 28 November 2008.

- ↑ 안또니오 네그리의 글모음

- ↑ Giovanni Fasanella and Alberto Franceschini (with a postscript from Judge Rosario Priore, who investigated on Aldo Moro's death), Che cosa sono le Red Brigades ("Who are the Red Brigades"), Published in French as Brigades rouges : L'histoire secrète des BR racontée par leur fondateur (Red Brigades: The secret [hi]story of the RBs, recounted by their founder), Alberto Franceschini, with Giovanni Fasanella. Editions Panama, 2005, ISBN 2755700203.

- ↑ Sporchi trucchi - "The CIA's anti-communist scheming in postwar Italy is well-documented, but the plot thickens with new revelations about British involvement." (1976 Foreign Office papers declassified. The Guardian, UK)

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Moore, Malcolm (March 11, 2008). "US envoy admits role in Aldo Moro killing". The Telegraph (London). http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/1581425/US-envoy-admits-role-in-Aldo-Moro-killing.html. Retrieved 2008-11-12.

- ↑ Arthur E. Rowse, "Gladio: The Secret US War to Subvert Italian Democracy", Covert Action Quarterly, Washington, DC, Number 49, Summer 1994.

- ↑ Moro's ghost haunts political life, Philip Willan in The Guardian, May 9, 2003

- ↑ Omicidio Pecorelli - Andreotti condannato, La Repubblica, 17 November 2002 (Italian)

- ↑ «Il Sismi tentò invano di salvare Moro», Corriere della Sera, 28 June 2008 (Italian)

- ↑ CARLOS: COSI' SALTO' L'ULTIMO TENTATIVO DI SALVARE ALDO MORO, ANSA (news agency), 28 June 2008 (Italian)

- ↑ Emmanuel Amara, Les derniers jours d'Aldo Moro (The Last Days of Aldo Moro), Interview of Steve Pieczenik put on-line by Rue 89

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Hubert Artus, Pourquoi le pouvoir italien a lâché Aldo Moro, exécuté en 1978 (Why the Italian Power let go of Aldo Moro, executed in 1978), Rue 89, 6 February 2008 (French)

- ↑ Emmanuel Amara, Les derniers jours d'Aldo Moro (The Last Days of Aldo Moro), Interview of Steve Pieczenik & Francesco Cossiga put on-line by Rue 89

- ↑ "Europa nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg:Freiheitliche Demokratien oder Satelliten der USA?" (in German). .zeit-fragen.ch. 2008-06-09. http://www.zeit-fragen.ch/ausgaben/2008/nr24-vom-962008/europa-nach-dem-zweiten-weltkrieg-freiheitliche-demokratien-oder-satelliten-der-usa/. Retrieved 2008-11-12.

- Interview with Giovanni Moro, Aldo Moro's son by La Repubblica, March 16, 1998.

- Giovanni Fasanella, Secret of State. The truth from Gladio to the Moro case (with G. Pellegrino, Einaudi, 2000)

- Giovanni Fasanella and Giuseppe Roca, The Mysterious Intermediary. Igor Markevitch and the Moro case (Einaudi, 2003)

- Gianfranco Sanguinetti, On Terrorism and the State

- Emmanuel Amara, Nous avons tué Aldo Moro, Paris: Patrick Robin, 2006, ISBN 2352280125.

Further reading

- Richard Drake (1996). The Aldo Moro Murder Case. Boston: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674014812.

External links

- Banca dati della memoria: Moro's letters and +

- Memorial Moro on strategy of tension

- Buongiorno, notte, 2003 film about the kidnapping

- Piazza Delle Cinque Lune, 2003 film about the kidnapping

- Italian document March 2, 1987

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Michele Di Pietro |

Italian Minister of Justice 1955–1957 |

Succeeded by Guido Gonella |

| Preceded by Paolo Rossi |

Italian Minister of Public Instruction 1957–1959 |

Succeeded by Giuseppe Medici |

| Preceded by Giovanni Leone |

Prime Minister of Italy 1963–1968 |

Succeeded by Giovanni Leone |

| Preceded by Giuseppe Saragat |

Italian Minister of Foreign Affairs 1964–1965 |

Succeeded by Amintore Fanfani |

| Preceded by Amintore Fanfani |

Italian Minister of Foreign Affairs 1965–1966 |

Succeeded by Amintore Fanfani |

| Preceded by Pietro Nenni |

Italian Minister of Foreign Affairs 1969–1972 |

Succeeded by Giuseppe Medici |

| Preceded by Giuseppe Medici |

Italian Minister of Foreign Affairs 1973–1974 |

Succeeded by Mariano Rumor |

| Preceded by Mariano Rumor |

Prime Minister of Italy 1974–1976 |

Succeeded by Giulio Andreotti |

| Preceded by Luigi Gui |

Italian Minister of the Interior 1976 |

Succeeded by Francesco Cossiga |

| Party political offices | ||

| Preceded by Amintore Fanfani |

Secretary of the Italian Christian Democracy 1959–1964 |

Succeeded by Mariano Rumor |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

.svg.png)